Frantz’s Story

Frantz is a 25-year-old young man from Colorado. His mom writes that until recently, he lived with the diagnosis of “hypotonic cerebral palsy with intellectual disability.” While that label helped him access the medical and academic supports he needed, it never fully captured his condition. Genetic testing at age four revealed no answers, but just recently, through Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS), Frantz received a diagnosis of CACNA1A variant c.4043G>C (p.Arg1348Pro). Talking with the genetic counselor was eye-opening, as one symptom after another matched the CACNA1A profile.

Variant: c.4043G>C (p.Arg1348Pro)

History

Frantz was a healthy 8 lbs at birth. He had some issues with regulating his body temperature in the first few days and had difficulty feeding (weak suck). However, these conditions resolved quickly, and there were no concerns until about 6-9 months, when I started noticing that he was falling short of typical milestones. I was assured by his pediatrician that there were no problems and that he was still in the normal range. At his one-year check-up, he was seen by a different doctor who immediately noted that Frantz’s presentation was not typical. This jump-started a whole series of evaluations and assessments that confirmed Frantz had a neuromuscular condition causing delays, but none of the medical tests–MRI, CAT scan, EEG, urinalysis, and blood work–provided any explanation for this. His initial diagnosis, by a Neurologist who said, “he’ll probably just be a little clumsy,” was Benign Congenital Myopathy. Even then, we knew it was probably a little more serious than that. Over the next six months, more evaluations were conducted, and concerns about his speech and cognitive processing were raised. The Neurodevelopmental Psychologist described his thinking as “fighting through a fog”. Fatigue and frustration were constant battles in Frantz’s daily life.

Milestones

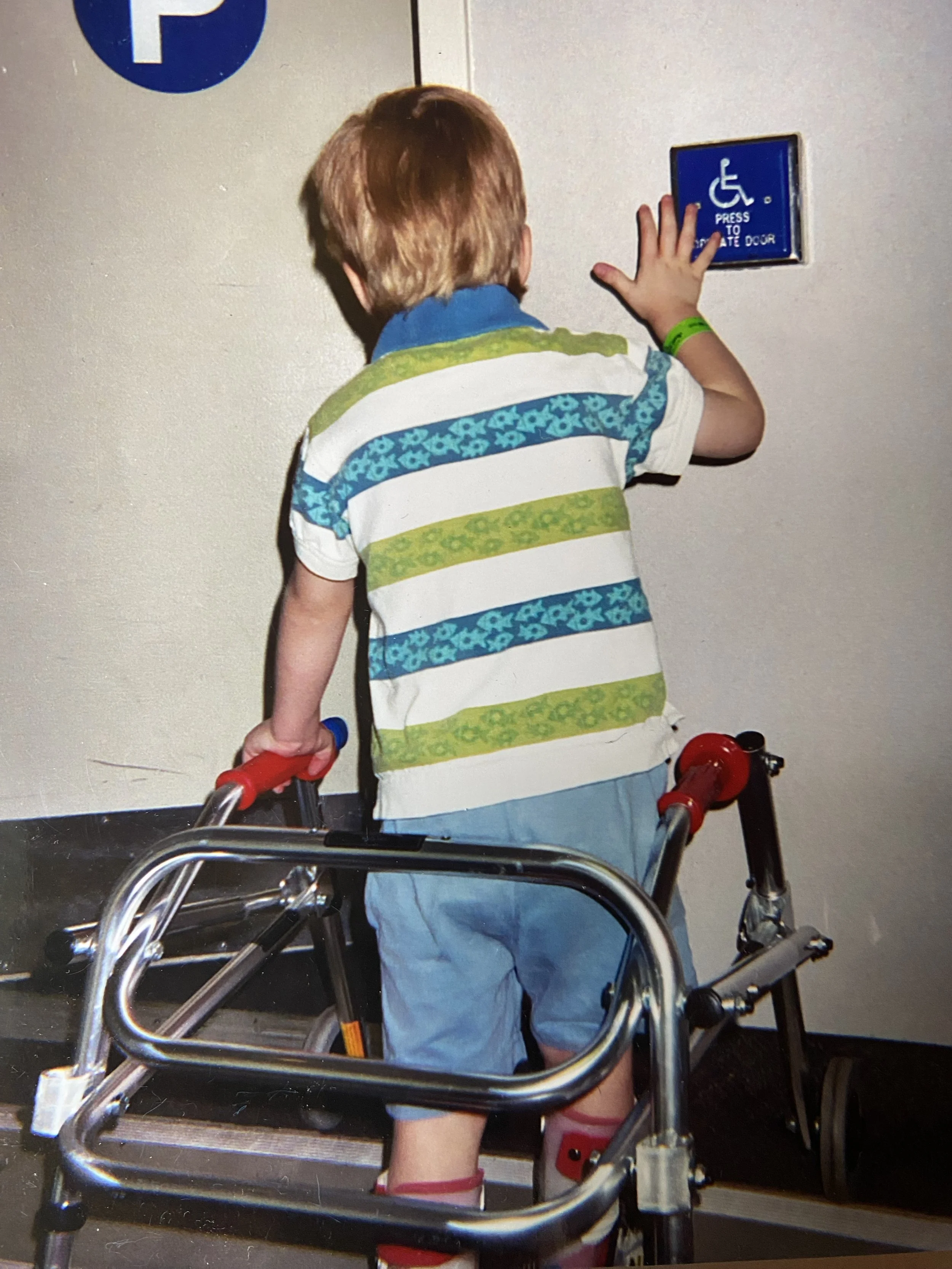

At 13 months, Frantz began “crawling”. It was described as a symmetrical commando crawl where he would reach forward with both arms and pull while pushing with both feet. At 14 months, he could sit briefly but would quickly collapse forward. He pulled up to stand at two years old, walked with a walker at six years, and took his first independent steps when he was nine years old. His first words were spoken at 18 months, he had 10 words at 2 years, 86 words and 30 signs at 3 years, and began speaking in short phrases by age four.

Therapies

Much of Frantz’s childhood revolved around therapy. He started PT at 13 months, OT at 16 months and speech therapy at 18 months. Later on, we added vision therapy, orofacial myofunctional therapy, sensory processing, and conductive education. We also sought out creative therapies that he loved, like aquatic therapy, adaptive skiing, music and art therapy, hippotherapy, and integrated therapy camps. While other children were busy with playdates, Frantz was often busy with therapy sessions. To make sure he still had opportunities to connect with peers, we brought the playdates to him, filling our home with activities—sandboxes, bouncy houses, and water play—that provided some normalcy to our lives.

Education

School was never straightforward. Every stage—elementary, middle, and high school—brought difficult decisions and advocacy battles. Sometimes inclusion was the priority; other times, safety or academics took precedence. There was never a “perfect” placement, only the best fit for that point in time. Frantz used a combination of a walker and a wheelchair to navigate at school until he was fifteen and entered high school. He had made up his mind that he was done wearing AFOs and using a walker. He was not very stable without these supports and had frequent falls, but did improve over time. Frantz thrived in high school. It was a welcoming environment where staff created a sense of belonging. He participated in supported inclusion, received individualized instruction, and found pride in helping run the school’s coffee shop and store—giving him both visibility and confidence. Frantz completed high school reading at a 3rd-4th grade level and having basic math skills. After that, he entered the 18–21 transition program, where he gained real-world skills in money management, public transit, and social interactions, while engaging in community experiences. Learning to navigate buses was daunting, given his balance challenges, but each small success built his independence. In his final year, he completed a supported internship at Children’s Hospital, where he gained valuable hands-on work experience.

Today

Through persistence, creativity, and community support, Frantz has grown into a capable and proud young man. He speaks fluently, although with some articulation challenges. He walks independently but has difficulty in snow/ice or uneven terrain and he requires a handrail to go up/down stairs. Frantz continues to find ways to adapt and overcome his cognitive processing challenges. Today, he works as an IT support specialist—a job that has been transformative for his confidence and independence. Frantz now lives in his own apartment (partially funded by a housing choice voucher) and is supported by an attendant who provides personal care and homemaker services through a Medicaid waiver. He takes Uber or Lyft to work through a subsidized paratransit program. Frantz actively participates in the community through supported programs, also funded through his Medicaid waiver. Most of all, he loves to play video games and never misses an opportunity to jump in a pool.

For Those Newly Diagnosed

I share Frantz’s story because I know how meaningful it is to see what’s possible, even when the journey doesn’t look like what we first imagined. Our kids may face barriers, but with advocacy, support, and the right opportunities, they can create lives filled with dignity, purpose, and joy.